By Susan Hutchinson

His passing, sudden and horrific, a drug-induced, homicidal savagery, sent ripples of outrage and grief throughout the congregation.

And this church, the promise of a humbler and purer way forward, was his way of attempting to cast aside the needled grip of drug life. And yet his search was answered in the cruelest of replies.

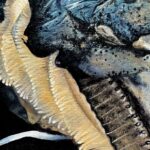

That turquoise and silver belt, a covenant of love made by his wife, was meant for wearing at sacred ceremony, not entre for another’s stolen passage into irreverent, unrelenting intoxication.

The robbery just one more ephemeral, transient high for Lucifer.

At the ultimate cost.

Those of us who knew him sensed his deep connection to the world of imagination and possibility. It would express itself in an abiding love of and connection to sculpture, and poetry, and the way in which these freeing forms reflected life’s twists and turns.

And wearing the belt as he sat in church, as he labored in the studio chiseling the granite block, as he formed phrases to pour his deepest hopes and fears into prose, made him feel whole.

He yearned to ignite those same imaginative potentials in his own life, sustainably, but would instead suffer from just too much loss, which proved insurmountable. Masking it with various addictive substances was like liar’s poker, and he knew it. The insidious strangle hold kept him from getting in front of it, and the price was paid.

The countless failed efforts to get there….

In the ways of his forefathers, he would invoke the spirit, strength, and resolve of a Higher Power, expressing his desire to take on elevated qualities and characteristics, looking to travel to worthy destinations, and away from those places he knew only too well, defined by staggering precipice.

He wanted to be more like Shackleton and Perry, Wordsworth and Whitman.

And when he was the man that we knew could show up, he was phenomenal.

He wore a sacred turquoise and silver belt.