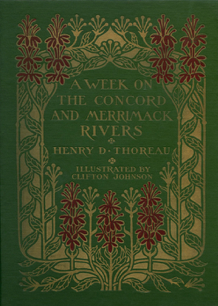

Middlesex Community College’s literary magazine’s name, Dead River Review, was inspired by passages from Henry David Thoreau’s book A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers published in 1849, which describes a canoe trip he and his brother John take on these two connected rivers that flow near MCC’s Bedford and Lowell campuses.

Reference #1: Bedford Campus

In the chapter “Sunday” of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, Thoreau describes waking Sunday morning from camping along the Concord River in Bedford, near MCC’s Bedford Campus, where the river widens so much that Thoreau compares it to a lake with water that is dead calm:

From Ball’s Hill to Billerica meeting-house, the river was still twice as broad as in

Concord, a deep, dark, and dead stream, flowing between gentle hills and

sometimes cliffs, and well wooded all the way. It was a long woodland lake

bordered with willows. (See longer excerpt from "Sunday" chapter below*.)

Reference #2: Lowell Campus

In the chapter “Saturday” of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, Thoreau writes of the large-scale death of fish on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers and the destruction of important fishing sites for Indigenous peoples (Pennacook, Pawtucket and Wamesit) when the industrial city of Lowell was created, with its dams and canals, on what had been Pawtucket and Wamesit Villages**. The American Shad was a very important fish for Indigenous people and for European settlers (once described as "the fish that fed the [American] nation's founders"), but due to the inability to reach their spawning grounds because of dams, the number of Shad harvested in the Merrimack River declined from almost 900,000 in 1789 to none in 1888. In 1849, Thoreau writes:

Shad are still taken in the basin of Concord River at Lowell, where they are said

to be a month earlier than the Merrimack shad, on account of the warmth of the

water. Still patiently, almost pathetically, with instinct not to be discouraged, not

to be reasoned with, revisiting their old haunts, as if their stern fates would relent,

and still met by the Corporation with its dam. Poor shad! where is thy redress?

When Nature gave thee instinct, gave she thee the heart to bear thy fate? Still

wandering the sea in thy scaly armor to inquire humbly at the mouths of rivers if

man has perchance left them free for thee to enter. By countless shoals loitering

uncertain meanwhile, merely stemming the tide there, in danger from sea foes in

spite of thy bright armor, awaiting new instructions, until the sands, until the

water itself, tell thee if it be so or not. Thus by whole migrating nations, full of

instinct, which is thy faith, in this backward spring, turned adrift, and perchance

knowest not where men do not dwell, where there are not factories, in these days.

Armed with no sword, no electric shock, but mere Shad, armed only with

innocence and a just cause, with tender dumb mouth only forward, and scales

easy to be detached. I for one am with thee, and who knows what may avail a

crow-bar against that Billerica dam?—Not despairing when whole myriads have

gone to feed those sea monsters during thy suspense, but still brave, indifferent,

on easy fin there, like shad reserved for higher destinies. Willing to be decimated

or man’s behoof after the spawning season. Away with the superficial and selfish

phil-anthropy of men,—who knows what admirable virtue of fishes may be below

low-water-mark, bearing up against a hard destiny, not admired by that fellow-

creature who alone can appreciate it! Who hears the fishes when they cry? It will

not be forgotten by some memory that we were contemporaries. Thou shalt

erelong have thy way up the rivers, up all the rivers of the globe, if I am not

mistaken. Yea, even thy dull watery dream shall be more than realized. If it were

not so, but thou wert to be overlooked at first and at last, then would not I take

their heaven. Yes, I say so, who think I know better than thou canst. Keep a stiff

fin then, and stem all the tides thou mayst meet.

**Note:

Seventeenth-century Indigenous life [along the Merrimack River] centered on

farming, hunting, and fishing. …The sources of power that enabled Lowell’s

industrialization—the dams and canals harnessing the Merrimack River—also were

a source of destruction. … [T]he building of dams and canals … impeded the

migratory patterns of fish [and] led to a rapid decline in the Native population.

(https://libguides.uml.edu/native_american_history/signage_project)

*Excerpts from:

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers

by Henry David Thoreau

from the “Sunday” chapter:

SUNDAY

“The river calmly flows,

Through shining banks, through lonely glen,

Where the owl shrieks, though ne’er the cheer of men

Has stirred its mute repose,

Still if you should walk there, you would go there again.”

—CHANNING.

“The Indians tell us of a beautiful River lying far to the south,

which they call Merrimack.”

—SIEUR DE MONTS, Relations of the jesuits, 1604.

In the morning the river and adjacent country were covered with a dense fog, through which the smoke of our fire curled up like a still subtiler mist; but before we had rowed many rods, the sun arose and the fog rapidly dispersed, leaving a slight steam only to curl along the surface of the water. It was a quiet Sunday morning, with more of the auroral rosy and white than of the yellow light in it, as if it dated from earlier than the fall of man, and still preserved a heathenish integrity:—

An early unconverted Saint,

Free from noontide or evening taint,

Heathen without reproach,

That did upon the civil day encroach,

And ever since its birth

Had trod the outskirts of the earth.

But the impressions which the morning makes vanish with its dews, and not even the most “persevering mortal” can preserve the memory of its freshness to mid-day. As we passed the various islands, or what were islands in the spring, rowing with our backs down stream, we gave names to them. The one on which we had camped we called Fox Island, and one fine densely wooded island surrounded by deep water and overrun by grape-vines, which looked like a mass of verdure and of flowers cast upon the waves, we named Grape Island. From Ball’s Hill to Billerica meeting-house, the river was still twice as broad as in Concord, a deep, dark, and dead stream, flowing between gentle hills and sometimes cliffs, and well wooded all the way. It was a long woodland lake bordered with willows. For long reaches we could see neither house nor cultivated field, nor any sign of the vicinity of man. Now we coasted along some shallow shore by the edge of a dense palisade of bulrushes, which straightly bounded the water as if clipt by art, reminding us of the reed forts of the East-Indians, of which we had read; and now the bank slightly raised was overhung with graceful grasses and various species of brake, whose downy stems stood closely grouped and naked as in a vase, while their heads spread several feet on either side. The dead limbs of the willow were rounded and adorned by the climbing mikania, Mikania scandens, which filled every crevice in the leafy bank, contrasting agreeably with the gray bark of its supporter and the balls of the button-bush. The water willow, Salix Purshiana, when it is of large size and entire, is the most graceful and ethereal of our trees. Its masses of light green foliage, piled one upon another to the height of twenty or thirty feet, seemed to float on the surface of the water, while the slight gray stems and the shore were hardly visible between them. No tree is so wedded to the water, and harmonizes so well with still streams. It is even more graceful than the weeping willow, or any pendulous trees, which dip their branches in the stream instead of being buoyed up by it. Its limbs curved outward over the surface as if attracted by it. It had not a New England but an Oriental character, reminding us of trim Persian gardens, of Haroun Alraschid, and the artificial lakes of the East.

As we thus dipped our way along between fresh masses of foliage overrun with the grape and smaller flowering vines, the surface was so calm, and both air and water so transparent, that the flight of a kingfisher or robin over the river was as distinctly seen reflected in the water below as in the air above. The birds seemed to flit through submerged groves, alighting on the yielding sprays, and their clear notes to come up from below. We were uncertain whether the water floated the land, or the land held the water in its bosom. It was such a season, in short, as that in which one of our Concord poets sailed on its stream, and sung its quiet glories.

“There is an inward voice, that in the stream

Sends forth its spirit to the listening ear,

And in a calm content it floweth on,

Like wisdom, welcome with its own respect.

Clear in its breast lie all these beauteous thoughts,

It doth receive the green and graceful trees,

And the gray rocks smile in its peaceful arms.”

And more he sung, but too serious for our page. For every oak and birch too growing on the hill-top, as well as for these elms and willows, we knew that there was a graceful ethereal and ideal tree making down from the roots, and sometimes Nature in high tides brings her mirror to its foot and makes it visible. The stillness was intense and almost conscious, as if it were a natural Sabbath, and we fancied that the morning was the evening of a celestial day. The air was so elastic and crystalline that it had the same effect on the landscape that a glass has on a picture, to give it an ideal remoteness and perfection. The landscape was clothed in a mild and quiet light, in which the woods and fences checkered and partitioned it with new regularity, and rough and uneven fields stretched away with lawn-like smoothness to the horizon, and the clouds, finely distinct and picturesque, seemed a fit drapery to hang over fairy-land. The world seemed decked for some holiday or prouder pageantry, with silken streamers flying, and the course of our lives to wind on before us like a green lane into a country maze, at the season when fruit-trees are in blossom.

Why should not our whole life and its scenery be actually thus fair and distinct? All our lives want a suitable background. They should at least, like the life of the anchorite, be as impressive to behold as objects in the desert, a broken shaft or crumbling mound against a limitless horizon. Character always secures for itself this advantage, and is thus distinct and unrelated to near or trivial objects, whether things or persons. On this same stream a maiden once sailed in my boat, thus unattended but by invisible guardians, and as she sat in the prow there was nothing but herself between the steersman and the sky. I could then say with the poet,—

“Sweet falls the summer air

Over her frame who sails with me;

Her way like that is beautifully free,

Her nature far more rare,

And is her constant heart of virgin purity.”

At evening still the very stars seem but this maiden’s emissaries and reporters of her progress.

Low in the eastern sky

Is set thy glancing eye;

And though its gracious light

Ne’er riseth to my sight,

Yet every star that climbs

Above the gnarled limbs

Of yonder hill,

Conveys thy gentle will.

Believe I knew thy thought,

And that the zephyrs brought

Thy kindest wishes through,

As mine they bear to you,

That some attentive cloud

Did pause amid the crowd

Over my head,

While gentle things were said.

Believe the thrushes sung,

And that the flower-bells rung,

That herbs exhaled their scent,

And beasts knew what was meant,

The trees a welcome waved,

And lakes their margins laved,

When thy free mind

To my retreat did wind.

It was a summer eve,

The air did gently heave

While yet a low-hung cloud

Thy eastern skies did shroud;

The lightning’s silent gleam,

Startling my drowsy dream,

Seemed like the flash

Under thy dark eyelash.

Still will I strive to be

As if thou wert with me;

Whatever path I take,

It shall be for thy sake,

Of gentle slope and wide,

As thou wert by my side,

Without a root

To trip thy gentle foot.

I’ll walk with gentle pace,

And choose the smoothest place

And careful dip the oar,

And shun the winding shore,

And gently steer my boat

Where water-lilies float,

And cardinal flowers

Stand in their sylvan bowers.

It required some rudeness to disturb with our boat the mirror-like surface of the water, in which every twig and blade of grass was so faithfully reflected; too faithfully indeed for art to imitate, for only Nature may exaggerate herself. The shallowest still water is unfathomable. Wherever the trees and skies are reflected, there is more than Atlantic depth, and no danger of fancy running aground. We notice that it required a separate intention of the eye, a more free and abstracted vision, to see the reflected trees and the sky, than to see the river bottom merely; and so are there manifold visions in the direction of every object, and even the most opaque reflect the heavens from their surface. Some men have their eyes naturally intended to the one and some to the other object.

“A man that looks on glass,

On it may stay his eye,

Or, if he pleaseth, through it pass,

And the heavens espy.”

Two men in a skiff, whom we passed hereabouts, floating buoyantly amid the reflections of the trees, like a feather in mid-air, or a leaf which is wafted gently from its twig to the water without turning over, seemed still in their element, and to have very delicately availed themselves of the natural laws. Their floating there was a beautiful and successful experiment in natural philosophy, and it served to ennoble in our eyes the art of navigation; for as birds fly and fishes swim, so these men sailed. It reminded us how much fairer and nobler all the actions of man might be, and that our life in its whole economy might be as beautiful as the fairest works of art or nature.

The sun lodged on the old gray cliffs, and glanced from every pad; the bulrushes and flags seemed to rejoice in the delicious light and air; the meadows were a-drinking at their leisure; the frogs sat meditating, all sabbath thoughts, summing up their week, with one eye out on the golden sun, and one toe upon a reed, eying the wondrous universe in which they act their part; the fishes swam more staid and soberly, as maidens go to church; shoals of golden and silver minnows rose to the surface to behold the heavens, and then sheered off into more sombre aisles; they swept by as if moved by one mind, continually gliding past each other, and yet preserving the form of their battalion unchanged, as if they were still embraced by the transparent membrane which held the spawn; a young band of brethren and sisters trying their new fins; now they wheeled, now shot ahead, and when we drove them to the shore and cut them off, they dexterously tacked and passed underneath the boat.

from the "Saturday" chapter:

SATURDAY

"Come, come, my lovely fair, and let us try

Those rural delicacies.”

—Christ’s Invitation to the Soul. QUARLES

. . .

Shad are still taken in the basin of Concord River at Lowell, where they are said to be a month earlier than the Merrimack shad, on account of the warmth of the water. Still patiently, almost pathetically, with instinct not to be discouraged, not to be reasoned with, revisiting their old haunts, as if their stern fates would relent, and still met by the Corporation with its dam. Poor shad! where is thy redress? When Nature gave thee instinct, gave she thee the heart to bear thy fate? Still wandering the sea in thy scaly armor to inquire humbly at the mouths of rivers if man has perchance left them free for thee to enter. By countless shoals loitering uncertain meanwhile, merely stemming the tide there, in danger from sea foes in spite of thy bright armor, awaiting new instructions, until the sands, until the water itself, tell thee if it be so or not. Thus by whole migrating nations, full of instinct, which is thy faith, in this backward spring, turned adrift, and perchance knowest not where men do not dwell, where there are not factories, in these days. Armed with no sword, no electric shock, but mere Shad, armed only with innocence and a just cause, with tender dumb mouth only forward, and scales easy to be detached. I for one am with thee, and who knows what may avail a crow-bar against that Billerica dam?—Not despairing when whole myriads have gone to feed those sea monsters during thy suspense, but still brave, indifferent, on easy fin there, like shad reserved for higher destinies. Willing to be decimated for man’s behoof after the spawning season. Away with the superficial and selfish phil-anthropy of men,—who knows what admirable virtue of fishes may be below low-water-mark, bearing up against a hard destiny, not admired by that fellow-creature who alone can appreciate it! Who hears the fishes when they cry? It will not be forgotten by some memory that we were contemporaries. Thou shalt erelong have thy way up the rivers, up all the rivers of the globe, if I am not mistaken. Yea, even thy dull watery dream shall be more than realized. If it were not so, but thou wert to be overlooked at first and at last, then would not I take their heaven. Yes, I say so, who think I know better than thou canst. Keep a stiff fin then, and stem all the tides thou mayst meet.

Some References:

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4232/pg4232-images.html

https://libguides.uml.edu/native_american_history/signage_project

https://www.lowelllandtrust.org/sites/default/files/PDF-files/crg_history_brochure.pdf

https://pubs.nps.gov/eTIC/LAMR-MANA/LOWE_475_131848_0001_of_0078.pdf

https://earlyamericanists.com/2019/06/18/damming-fish-and-indians-starvation-and-dispossession-in-colonial-massachusetts/